Harmonic measure

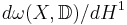

In mathematics, especially potential theory, harmonic measure is a concept related to the theory of harmonic functions that arises from the solution of the classical Dirichlet problem. In probability theory, harmonic measure of a bounded domain in Euclidean space  ,

,  is the probability that a Brownian motion started inside a domain hits a portion of the boundary. More generally, harmonic measure of an Itō diffusion X describes the distribution of X as it hits the boundary of D. In the complex plane, harmonic measure can be used to estimate the modulus of an analytic function inside a domain D given bounds on the modulus on the boundary of the domain; a special case of this principle is Hadamard's Three-circle theorem. On simply connected planar domains, there is a close connection between harmonic measure and the theory of conformal maps.

is the probability that a Brownian motion started inside a domain hits a portion of the boundary. More generally, harmonic measure of an Itō diffusion X describes the distribution of X as it hits the boundary of D. In the complex plane, harmonic measure can be used to estimate the modulus of an analytic function inside a domain D given bounds on the modulus on the boundary of the domain; a special case of this principle is Hadamard's Three-circle theorem. On simply connected planar domains, there is a close connection between harmonic measure and the theory of conformal maps.

The term harmonic measure was introduced by R. Nevanlinna in 1934 for planar domains,[1] although Nevanlinna notes the idea appeared implicitly in earlier work by Johansson, F. Riesz, M. Riesz, Carleman, Ostrowski and Julia (original order cited). The connection between harmonic measure and Brownian motion was first identified by Kakutani ten years later in 1944 [2]

Contents |

Definition

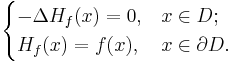

Let D be a bounded, open domain in n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn, n ≥ 2, and let ∂D denote the boundary of D. Any continuous function f : ∂D → R determines a unique harmonic function Hf that solves the Dirichlet problem

If a point x ∈ D is fixed, by the Riesz representation theorem and the maximum principle Hf(x) determines a probability measure ω(x, D) on ∂D by

The measure ω(x, D) is called the harmonic measure (of the domain D with pole at x).

Properties

- For any Borel subset E of ∂D, the harmonic measure ω(x, D)(E) is equal to the value at x of the solution to the Dirichlet problem with boundary data equal to the indicator function of E.

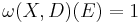

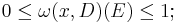

- For fixed D and E ⊆ ∂D, ω(x, D)(E) is an harmonic function of x ∈ D and

- Hence, for each x and D, ω(x, D) is a probability measure on ∂D.

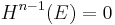

- If ω(x, D)(E) = 0 at even a single point x of D, then y

ω(y, D)(E) is identically zero, in which case E is said to be a set of harmonic measure zero. This is a consequence of Harnack's inequality.

ω(y, D)(E) is identically zero, in which case E is said to be a set of harmonic measure zero. This is a consequence of Harnack's inequality.

Since explicit formulas for harmonic measure are not typically available, we are interested in determining conditions which guarantee a set has harmonic measure zero.

- F. and M. Riesz Theorem[3]: If

is a simply connected planar domain bounded by a rectifiable curve (i.e. if

is a simply connected planar domain bounded by a rectifiable curve (i.e. if  ), then harmonic measure is mutually absolutely continuous with respect to arc length: for all

), then harmonic measure is mutually absolutely continuous with respect to arc length: for all  ,

,  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

- Makarov's theorem[4]: Let

be a simply connected planar domain. If

be a simply connected planar domain. If  and

and  for some

for some  , then

, then  . Moreover, harmonic measure on D is mutually singular with respect to t-dimensional Hausdorff measure for all t>1.

. Moreover, harmonic measure on D is mutually singular with respect to t-dimensional Hausdorff measure for all t>1.

- Dahlberg's theorem[5]: If

is a bounded Lipschitz domain, then harmonic measure and (n-1)-dimensional Hausdorff measure are mutually absolutely continuous: for all

is a bounded Lipschitz domain, then harmonic measure and (n-1)-dimensional Hausdorff measure are mutually absolutely continuous: for all  ,

,  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

Examples

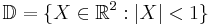

- If

is the unit disk, then harmonic measure of

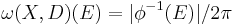

is the unit disk, then harmonic measure of  with pole at the origin is length measure on the unit circle normalized to be a probability, i.e.

with pole at the origin is length measure on the unit circle normalized to be a probability, i.e.  for all

for all  where

where  denotes the length of

denotes the length of  .

.

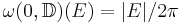

- If

is the unit disk and

is the unit disk and  , then

, then  for all

for all  where

where  denotes length measure on the unit circle. The Radon-Nikodym derivative

denotes length measure on the unit circle. The Radon-Nikodym derivative  is called the Poisson kernel.

is called the Poisson kernel.

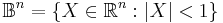

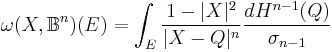

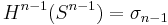

- More generally, if

and

and  is the n-dimensional unit ball, then harmonic measure with pole at

is the n-dimensional unit ball, then harmonic measure with pole at  is

is  for all

for all  where

where  denotes surface measure (

denotes surface measure ( -dimensional Hausdorff measure) on the unit sphere

-dimensional Hausdorff measure) on the unit sphere  and

and  .

.

- If

is a simply connected planar domain bounded by a Jordan curve and X

is a simply connected planar domain bounded by a Jordan curve and X D, then

D, then  for all

for all  where

where  is the unique Riemann map which sends the origin to X, i.e.

is the unique Riemann map which sends the origin to X, i.e.  . See Carathéodory's theorem.

. See Carathéodory's theorem.

- If

is the domain bounded by the Koch snowflake, then there exists a subset

is the domain bounded by the Koch snowflake, then there exists a subset  of the Koch snowflake such that

of the Koch snowflake such that  has zero length (

has zero length ( ) and full harmonic measure

) and full harmonic measure  .

.

The harmonic measure of a diffusion

Consider an Rn-valued Itō diffusion X starting at some point x in the interior of a domain D, with law Px. Suppose that one wishes to know the distribution of the points at which X exits D. For example, canonical Brownian motion B on the real line starting at 0 exits the interval (−1, +1) at −1 with probability ½ and at +1 with probability ½, so Bτ(−1, +1) is uniformly distributed on the set {−1, +1}.

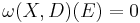

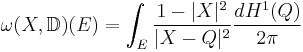

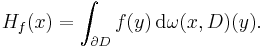

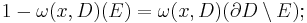

In general, if G is compactly embedded within Rn, then the harmonic measure (or hitting distribution) of X on the boundary ∂G of G is the measure μGx defined by

for x ∈ G and F ⊆ ∂G.

Returning to the earlier example of Brownian motion, one can show that if B is a Brownian motion in Rn starting at x ∈ Rn and D ⊂ Rn is an open ball centred on x, then the harmonic measure of B on ∂D is invariant under all rotations of D about x and coincides with the normalized surface measure on ∂D

General References

- Garnett, John B.; Marshall, Donald E. (2005). Harmonic Measure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.2277/0521470188. ISBN 9780521470186.

- Øksendal, Bernt K. (2003). Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications (Sixth ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-04758-1. MR2001996 (See Sections 7, 8 and 9)

References

- ^ R. Nevanlinna (1934), "Das harmonische Mass von Punktmengen und seine Anwendung in der Funktionentheorie", Comptes rendus du huitème congrès des mathématiciens scandinaves, Stockholm, pp. 116-133.

- ^ Kakutani, S. (1944). "On Brownian motion in n-space". Proc. Imp. Acad. Tokyo 20 (9): 648–652. doi:10.3792/pia/1195572742.

- ^ F. and M. Riesz (1916), "Über die Randwerte einer analytischen Funktion", Quatrième Congrès des Mathématiciens Scandinaves, Stockholm, pp. 27-44.

- ^ Makarov, N. G. (1985). "On the Distortion of Boundary Sets Under Conformal Maps". Proc. London Math. Soc.. 3 52 (2): 369–384. doi:10.1112/plms/s3-51.2.369.

- ^ Dahlberg, Björn E. J. (1977). "Estimates of harmonic measure". Arch. Rat. Mech. Anal. 65 (3): 275–288. Bibcode 1977ArRMA..65..275D. doi:10.1007/BF00280445.

External links

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Harmonic measure", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=H/h046500

![\mu_{G}^{x} (F) = \mathbf{P}^{x} \big[ X_{\tau_{G}} \in F \big]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/25e023994c634080e11c457450452848.png)